The National Trust’s race problem

Hilary McGrady recently told MPs

There is still a painful truth that the vast majority of people who work in the heritage sector still identify as white—over 90%. We are not representative of the communities we serve. Equally, I know from our membership base that we are improving. We are up to something like 22% from diverse communities. That is still not where we need to be, so I think it is a very real challenge for us.

Meanwhile, a member of what Mrs McGrady would call ‘diverse communities’ has been to visit Upton House is and dismayed to see people like her treated as members of identity groups an not as individuals. Our visitor produced this account of the experience:

Descriptions such as this one rely on speculation, take an activist point of view and make assumptions about the interests of ethnic minority visitors

Over-reading Race? The Limits of Political Interpretation in Historical Imagery

The National Trust uses modern racial interpretive frameworks which over-simplify historical nuance and impose speculative or ideological readings on viewers, leaving no room for visitors to make sense of the facts for themselves and base on them their own ideas, opinions and criticisms about the art.

There is a growing tendency to interpret 18th-century artworks featuring black figures through the lens of slavery and oppression, even when the artwork does not overtly depict such themes. The presence of a black person in a painting from this period often leads to the assumption that they must represent servitude or white dominance. Once this assumption is made, it becomes easy to steer the interpretation toward discussions of slavery and systemic injustice, regardless of what the artwork appears to show. We should acknowledge historical contexts, but remain cautious about imposing modern political narratives onto artworks without good evidence. This tendency—common in some museum and heritage settings—risks weakening the integrity of art interpretation by prioritising ideological messaging over careful analysis.

Upton House in Warwickshire

In May 2025, I visited Upton house in Warwickshire, a seventeenth-century country house which was given a makeover in the early twentieth century with the addition of impressive gardens and a superb art collection. A collection of eighteenth-century Sèvres porcelain in glass cases particularly caught my eye. The designs were intriguing: the artists contrasted the glamorous, luxurious designs and extraordinary curvature with art that depicted everyday 18th-century scenes such as farming and sailors loading ships. A bowl decorated with a harbour scene showed a group of sailors preparing to load goods for shipping. A notice described ‘a group of pristinely dressed sailors’ and the narrowed the focus onto a single black dockworker. If there is a black person in the art, must one always talk about his race? I would say, only if the artwork itself places a sort of emphasis on the race of the individual. In this label, the writer highlights the symbolic meaning of blackness in, I assume, eighteenth-century Britain, saying ‘the idea of blackness became a symbol of servitude’ and that black people ‘were reduced to symbols of white influence’ in portraiture. While this may have been true in many instances, if one is going to focus on race, some nuance is necessary. After all, the notice states that ‘it’s not clear if the sailor shown is free or enslaved’. This is quite an important detail as the status of the individual would have made a difference to how he was perceived.

A porcelain cup and cover at Upton House

This is a work of art, not a crude cartoon, and as such it portrays a complicated reality, not all of which we necessarily understand today. As a black person myself who has been educated on the varied and complicated lives of my ancestors, I would expect curators to describe these scenes rather carefully based on what is objectively known or what can be directly inferred from the piece beyond a reasonable doubt. No one likes to be the subject of generalisation, and if something is commonplace, this does not mean that it was always the case. I understand that being objective is very difficult when one has little information or context about these pieces to go by, but the least that the writer could have done was explain that black people were not always symbols of servitude or white influence in 18th-century portraiture. Take for example Thomas Gainsborough’s 1768 portrait of the very respected Ignatius Sancho (c.1729-1780): though he was a valet to the Duke of Montagu, in this portrait, he was depicted not ‘as an enslaved person, servant or caricature, but as a gentleman’. He was able to transcend his status as a valet by running grocer’s in Westminster whilst simultaneously supporting and contributing to the abolitionist movement. Sancho was also the first black man to receive an obituary in the British press. The existence of black individuals like Sancho discredits labels that characterise all black people as symbols of servitude. Many black people were able to transcend this status and become respected in their own right.

On this label, the subject of race is dominant and everything else has been pushed out. Something could have been said about the material, the significance of Sèvres, its creation in France for French customers, why dockworkers were being displayed and perhaps the significance of the contrast between the luxurious Sèvres and the everyday scene. Not only here, but in several museums recently I have seen is what appears to be an effort to over-compensate or over-explain the presence of black people, which results in blowing their presence out of proportion to the point of generalisation. This takes away from the overall significance of the art and amounts to the expression of a political views and the descriptions go beyond what is objectively known about the art.

Eighteenth-century plaster figures at Packwood House

The need to speculate about racial tensions within art was also evident in a label accompanying a pair of plaster figures at Packwood House, dated between 1720 and 1740. The label’s author explicitly admits knowing ‘very little about the object’, yet goes on to speculate extensively about power dynamics between the white woman and the black boy depicted. Viewers are encouraged to interpret the relationship as one of dominance and subjugation based on visual cues alone, namely, the woman ‘adorned in pearls and fine clothes’ and the boy in ‘exotic’ attire. This reading assumes that any depiction of racial difference necessarily signifies inequality, reinforcing the binary framework where whiteness is linked to privilege and blackness to oppression. Again, this might have been the case, but the viewer should be offered evidence rather than just opinion. The relationship between them may well have been more nuanced. It seems unlikely that the artists set out to show racial tension, and we would do better to start by focussing on what the artist intended us to see before speculating further.

By prioritising assumptions over evidence the curator imposes a particular interpretation on the viewer. The audience is directed towards a predetermined moral conclusion and implicitly instructed to view the figures through the lens of racial injustice. In doing so, it shifts the focus away from the artwork itself and onto the writer’s sociopolitical critique. This approach not only imposes a narrow reading but also risks dehumanising the figures by reducing them to racial types rather than leaving open the possibility of individuality and agency. What is particularly troubling is that this mode of interpretation mirrors the very essentialist thinking it claims to resist. By assuming that black figures in art must represent subjugation, it perpetuates a simplistic narrative in which blackness is always associated with victimhood and whiteness with authority. Such binary thinking overlooks the diverse roles black individuals played in European history and denies the possibility of alternative relationships and identities beyond domination and submission.

Encouragingly, Packwood House has since updated this label. The revised version provides a far more nuanced and evidence-based interpretation. It explains that Baron Ash, the collector, believed the figures originated from an Italian nativity scene, and contextualises them as possibly representing everyday characters or even fashion dolls used to display contemporary dress. While race is still acknowledged, it is not the overriding lens through which the artefacts are interpreted. The focus is instead placed on material history, provenance, and artistic context, allowing the viewer to engage with the piece on multiple levels. This revised approach avoids the trap of binary racial thinking. It invites the audience to consider a wider range of historical possibilities, emphasising uncertainty over speculation and complexity over ideological clarity. In doing so, it restores both the integrity of the artwork and the agency of those represented. Ultimately, when institutions default to binary racial narratives, they risk replicating the very structures of essentialism they seek to critique. A more careful, nuanced approach, one grounded in research rather than assumption, does not ignore histories of oppression but resists the temptation to project them onto every artefact uncritically. Only by challenging these binaries can we begin to recover the full complexity of the past.

Another consequence of only seeing art through racial terms when they depict a black person is this: viewers are left to speculate about the actual art on display as we are told very little about it. The Sèvres bowl was produced in France, and this raises the question of how black people were seen in France. Was their position any different from that of black people in England? The writer makes assumptions about the individual without actually substantiating them. We simply don’t know how the artist viewed this black dockworker, who could have been an Ignatius Sancho for all I know. The label stated that the black person ‘receives instruction’. It is not clear that receiving instruction must necessarily imply servitude. We just do not know. What we do know is that there was a wide variety of roles and statuses within black populations in the eighteenth century.

Porcelain at Upton House

There have been some changes to the labelling at Upton House as well. In 2023 a cup was described as follows:

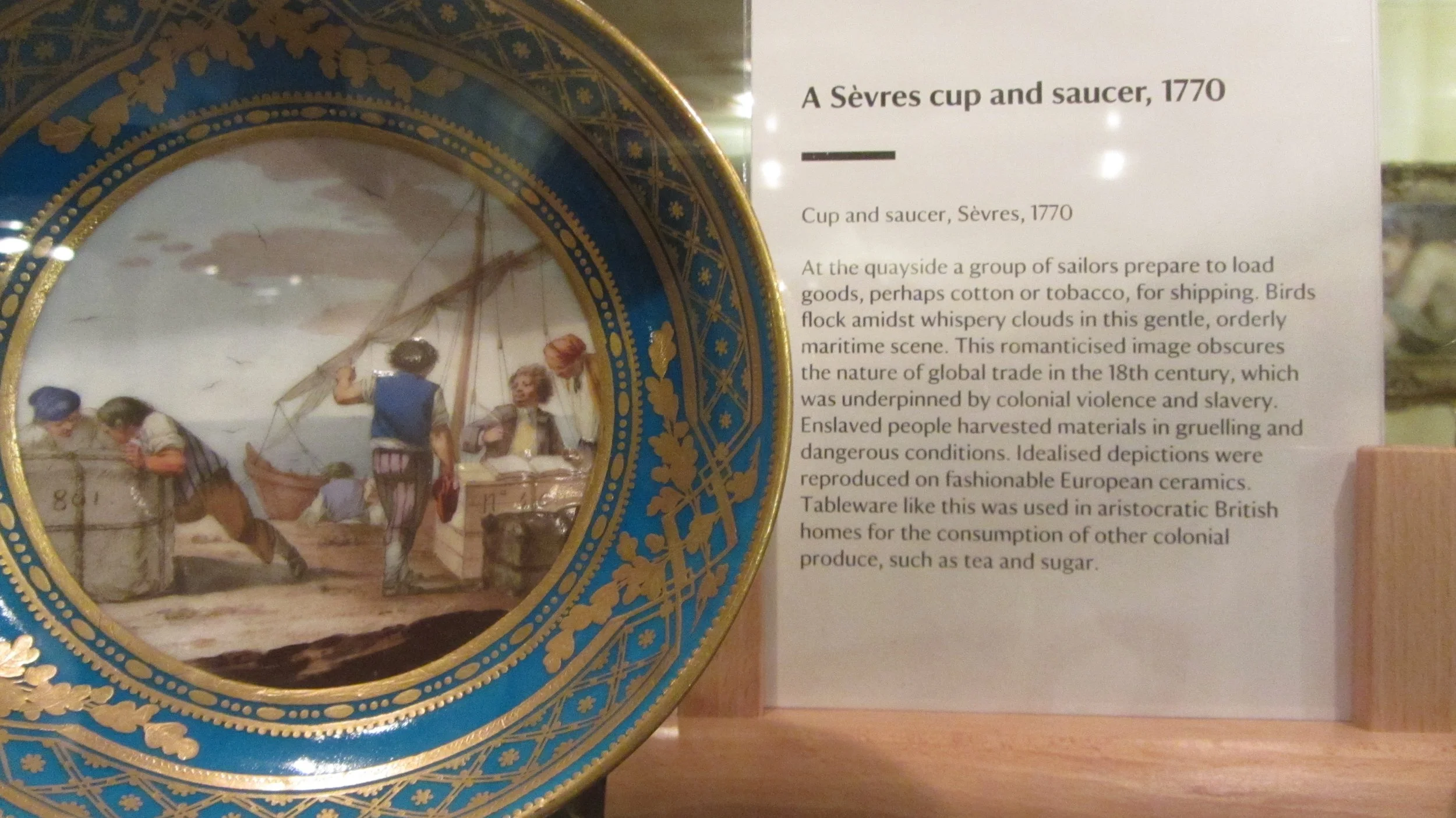

‘Cup and Saucer, Sèvres, 1770. At the quayside a group of sailors prepares to load goods, perhaps cotton or tobacco, for shipping. Birds flock amidst whispery clouds in this gentle, orderly maritime scene. This romanticised image obscures the nature of global trade in the 18th century, which was underpinned by colonial violence and slavery. Enslaved people harvested materials in gruelling and dangerous conditions. Idealised depictions were reproduced on fashionable European ceramics. Tableware like this was used in aristocratic British homes for the consumption of other colonial produce, such as tea and sugar.’

The writer deviates from what is being portrayed in the art, retreating to, once again, mere speculation about how the piece connects to slavery. Although I agree with the writer that ‘global trade in the 18th century was underpinned by colonial violence and slavery’, and that slaves ‘harvested materials in gruelling and dangerous conditions’, the writer is axiomatically speculating about matters that go beyond the art. The writer describes the art as a ‘romanticised image’ that obscures the nature of global trade in the 18th century”; this is an opinion that assumes that the artist intended to hide the true nature of 18th-century global trade, or to even depict global trade. It is not a curator’s place to second-guess the artist’s intention. Leave that up to viewers. It isn’t the role of curators to force their suspicions and political viewpoints down the reader’s throat. As the American commentator Michael Savage says, ‘Curators play a vital role in selecting, displaying and interpreting’. In fact, this is all that we expect from curators. Savage says quire rightly that we do not, however, ‘go to museums to be indoctrinated’, that is to say, have opinions imposed on us. We want to form our interpretations of the piece; we do not need curators to tell us how to conceive of something. What if this was simply the artist’s portrayal of what he genuinely saw? The fact that the art does not depict noticeably horrific scenes does not make it a false representation of reality or a mere façade. It also does not mean that global trade always looked like this and was not horrific; we all know that it was. The problem here is that the art is being used as a means to an end. That is, it is being used to further the personal viewpoints and opinions of the writer on behalf of the National Trust. Assumptions are being made to allow the writer to build a connection between general 18th-century societal trends and this particular piece of art, even though it is not necessarily the case that the two are connected. Rather than offering an informative and objective description of the piece, the writer offers a political critique. Why is valuable space on the label being used to advance activist speculation rather than inform readers about what is being portrayed? One can agree that conditions for the enslaved were brutal and that much of the portraiture at the time in which this art piece was produced was romanticised, whilst also acknowledging that this cannot directly be inferred from the piece of art under examination. In other words, the writer formulates hedged statements that build toward strong moral conclusions. We need to stop drawing weak connections between general historical facts about race and very peculiar artistic portrayals of events that we know little about. Such implication without evidence undermines the historical credibility of the interpretation. When talking about race, a distinction between inference and proof must be made and that proof is always prioritised. It seems as though whenever a black person or a person of colour is in the presence of white people, tension needs to be highlighted and explained—even if there is no objectively known tension in the piece. There seems to be a need to virtue-signal by linking black people to oppression and subjugation. Since this label was no longer there when I visited Upton House in 2025, perhaps someone at the National Trust is beginning to understand that there is a problem with this kind of speculative labelling. However, as we saw in the label describing the piece which shows the black dockworker, there is apparently still a need to generalise on racial matters when a black person is depicted.

Flattening Complexity: Binary Thinking in Racial Narratives

A painting of Thomas Smith and his family attributed to Robert West in Upton House

Another piece of art that stood out for me was a painting of 1733 showing Thomas Smith and his family taking tea in their drawing room, attended by a black servant. Until last year there was a label attached to the wall under the picture, devoted mostly to the minor figure of a black servant and written largely through the narrow lens of slavery and colonialism. The author speculates about slavery and race, but doesn’t tell us much about the piece of art. I was interested in the ladies’ clothes, the significance of the tea the boy was pouring, the miniature cups, where the boy might have been from and why he was wearing what looked like Middle Eastern dress. Fair enough, there isn’t room for everything on a label, but it is hard to see how the content that did make it onto the notice was justified:

‘Resplendent in their finest clothes, the Smiths take Tea. To the side, a young man observes, waiting with a grand silver kettle on its stand.

In the 18th century, an increasing number of black servants featured in portraits as symbols of their master’s [sic] wealth and global connections. Often positioned in the corner of an image, black people are portrayed in a subservient pose, wearing lavish dress.

While the servant remains unnamed, it’s possible that the family are the Smiths of Hadley, Middlesex. The eldest Smith son, Thomas (d. 1798), owned two plantations worked by enslaved people in Grenada.’

Detail from the portrait of Thomas Smith and his family

To me, the race and status of the black boy are not interesting to the exclusion of all else. Leaving slavery and race to one side, we are told almost nothing about the painting.

In 2025 neatly bound hand lists appeared in the house, with this new description.

‘In this picture, Thomas Smith and his wife are shown surrounded by their family. Smith’s original name was Le Favre and he was of French extraction.

The inclusion of a black attendant in the image at this time, often in fanciful dress, was seen as an expression of the wealth and status of the family. It is not known if the attendant, who is of African descent, was included by the artist as a trope or as a portrait of a real individual.

The artist is probably Robert West. Little is known about him except hat he studied in Paris under the artist Van Loo, and in about 1744 established a drawing school in Dublin.’

In the new description we are told more about Thomas Smith and the more speculative observations regarding slavery have been omitted. Instead, there is more factual information about black servants in such portraits, as well as information about the artist. What a difference. This label is both matter-of-fact and much more informative. The writer is not bound by the narrow paradigm through which the Trust has become accustomed to viewing and interpreting art. This is how it should be done!

The writers of the labels that I have highlighted seem to express their distaste for the artists and the artwork by including historical information heavily focussed on race which, though factually correct in itself, is not the most relevant to the artwork in question. An interpretative framework, and, indeed, an attempt at psychoanalysis is being imposed on the viewer. In allowing or encouraging this, the National Trust oversteps a boundary that separates what the custodian of the art can and should offer the public by way of guiding appreciation and what is up to the personal interests of the viewer. To put it another way, activism or proselytising perverts the purpose of displaying art to the public.

Diversity and Inclusion in the National Trust

The National Trust has expressed its desire to become more inclusive and attract people from all communities, more specifically, people from ethnic minority backgrounds. In other words, they want more people who look like me to visit their properties. An article published in the National Trust Magazine in 2020, refers to a report which ‘outlined that systemic and institutional racism was prevalent’ in voluntary organisations, presumably including the National Trust and went on to claim, ‘We have a duty to play our part in creating a fairer, more equitable society’. From this two objectives arise, firstly, to ‘make sure everyone feels welcome at the National Trust’ and, secondly, ‘to present the colonial history of our places in a thoughtful way that promotes productive debate and reflection’. Hilary McGrady, Director-General of the National Trust, said in 2023 that the National Trust’s charitable purpose ‘to preserve nature, beauty and history for the benefit of the nation’ can only be achieved ‘if we reflect the nations and communities we serve’. This is where I think the first problem arises with the Trust’s means of achieving diversity, whilst upholding the integrity of this charitable purpose. McGrady’s assertion implies that the Trust is simply manipulating the meaning of the art in its collections so that it aligns with what Trust employees imagine to be the desires and viewpoints of the ‘diverse communities’ they want to attract. If this is the case, then they are already failing to serve serving ‘the nation’, as they have sacrificed doing this in order to please a particular sub-sector of society.

The second problem relates to the National Trust’s continual tendency to put ethnic minority people in a single box. We are not an indistinct mass. Just because we look similar we do not all think the same way or want the same things. And yet, this is what the National Trust seems to assume when every image of a black person is reduced to a reference to slavery or colonialism. I do not go to museums to be told repeatedly, whenever black people are shown in art, how insignificant we were and how offended we should feel about what is on display. This treatment feels somewhat discriminatory as it rests on the assumption that we cannot handle seeing the art and therefore need reassurance or validation of some sort. Even worse, as an art enthusiast, I visit museums and Trust properties to admire art; the experience is diminished when some presumed link to colonialism or slavery becomes the main focus of the piece, as if I cannot possibly be more interested in the qualities that interest most art enthusiasts, such as, say, the brushwork or the composition. All this does to me, as a black person, is make me more inclined to feel like a target simply by virtue of my race.

The presentation of colonial history becomes problematic when a single perspective is promoted. The hoped-for ‘debate and reflection’ is likely to become narrow as other perspectives are not considered. This is why I believe that the promotion of what they call ‘productive debate’ is not compatible with the National Trust’s purpose. What makes a debate ‘productive’? Based on what I have seen, it seems to me to mean that people should view the art through the lens of race-based victimhood. In this sense, ‘productive debate’ has been promoted when audiences have been indoctrinated. The American political commentator Michael Savage offers an accurate analysis when he says that though museums ‘cannot be neutral’ as ‘nothing interesting is neutral’, this is ‘not an excuse for asserting partisan control, turning museums into instruments for engineering a right-thinking progressive citizenry’. He says that doing this will only alienate visitors even more, in turn, provoking backlash. More alarmingly, he questions whether ‘we want left-wing museums and separate right-wing museums, or museums contested between radical and conservative curators’. This is the natural endpoint of the path taken by the National Trust, and yet we must avoid this outcome if the Trust is to be truly ‘National’.

Speculation as an argument does not work; it replaces objectivity. The less objective one is about art, the more remote the possibility of transmitting appreciation and understanding. Inclusion and greater ethnic minority awareness of the Trust is not going to be achieved through virtue signalling, over-generalising the black experience or the meaning of blackness, and taking away from the art or crucial information that is relevant to the art, to signal to us how negative or offended we should be at the art. It is achieved by accurately and confidently interpreting the art without insinuation or partisanship. Leave the viewers to form their own opinions, and to take sides if they wish. When interpreting people of colour, be relevant and objective. There is no need to validate our presumed sensitive emotions, or to virtue-signal. Don’t expect us feel like we need a helping hand.